Let me admit something, right up front. Writing for this blog topic has been difficult. Not because of the topic, but because how to you fit 200+ years of inequality into a 500-word post…in all honesty you don’t. So, the first thing we must discuss right up front, is the breadth of this topic in general, and the history of systemic racism that persists and often goes unrecognized and undiscussed. This blog will never be able to cover it all, but hopefully give us a moment of pause and reflection. Coming to terms with that first fact is a great first steppingstone to understanding how and why racial disproportionality exist and is so rampant in child welfare.

Every Decision

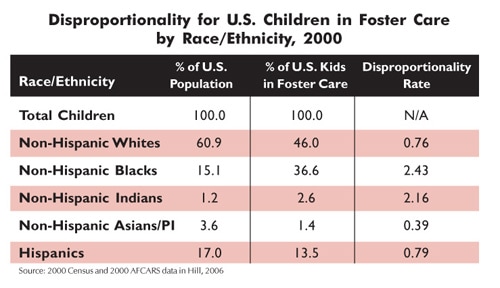

What we know is that racial disparities occur at EVERY decision-making point along the child welfare continuum. It begins with who is reported in the first place. Statistically, we know a majority of mandatory reporters are white. We know that white mandatory reporters are more likely to report families of color to police and/or child welfare agencies at much higher rates for similar behavior they witness in white families.At the national level, black families are overrepresented in reports of suspected maltreatment (Krase, 2013). They are also subjected to child protective services investigations at higher rates than other families (Kim et al., 2017). Additionally, black and indigenous children are at a greater risk than other children of being confirmed for maltreatment and placed in out of home care (Yi et al., 2020).

We also need to understand that while some groups are overrepresented, some are underrepresented, particularly Asian and white children. It is believed that this underreporting is tied again to racial bias and disparities on our individual perceptions of those cultural and racial perceptions of behavior.

We previously mentioned structural racism as one of the causes, but there are many others as well, including but not limited to:

- racial bias and discrimination exhibited by individuals involved,

- policy and legislation,

- lack of resources for families of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds,

- geographic context,

- and bias on the views and understanding of poverty in general.

What can we do?

As the saying goes, admitting we have a problem is the first step. But what can individuals do? First, we need to be able to talk freely and openly about our own individual bias. We all have them. To look at your own biases, take this free quiz on the Project Implicit website. This is a great first step for everyone to take!

For child welfare, there are lots of places to begin this work, but here are a few suggestions:

- invest in assessment, training, and technical assistance for cultural responsiveness,

- develop ways to measure racial equity in agency programs and outcomes,

- involve members of impacted communities in the review and revision process,

- find out how to get involved in statewide legislation and policy decisions,

- invest in early interventions,

- utilize cross-system collaboration,

- create community councils,

- increase investments in reunification services,

- promote permanency options,

- prioritize quality legal representation and court oversight,

- develop a culturally responsible and diverse workforce,

- create community partnerships,

- develop culturally specific and responsive services,

- include families in group decision making,

- create parent partner programs,

- utilize cultural broker programs,

- recruit resource families,

- and so, so many others.

We cannot ignore racial disproportionality.

We cannot ignore racial disproportionality. As the science continues to develop around early childhood trauma and racial trauma, we know we must confront this unjust and pervasive issue once and for all. Although there is conflicting data about the causes, we know that there are promising practices that use antiracist and culturally specific approaches to directly address them. When all else fails, we can at least begin to address the bias within ourselves.

References:

Krase, K. S. (2013). Differences in racially disproportionate reporting of child maltreatment across report sources. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 7, 351–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2013.79 8763

Kim, H., Wildeman, C., Jonson-Reid, M., & Drake, B. (2017). Lifetime prevalence of investigating child maltreatment among US children. American Journal of Public Health, 107, 274–280. https://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5227926/

Yi, Y., Edwards, F. R., & Wildeman, C. (2020). Cumulative prevalence of confirmed maltreatment and foster care placements for US children by race/ethnicity, 2011-2016. American Journal of Public Health, 110, 704–709. https://www.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305554