Understanding Experiential Learning vs. Experiential Education

Several years ago, I became the Director of Experiential Learning at Crossnore. Since then, I have often questioned what my title truly entails. I love my title and appreciate the intent behind it. In this post, I will discuss the difference between experiential learning and education, provide examples, and highlight their impact on young people.

Experiential learning and experiential education are not synonymous. Learning happens continuously, but learning through experience does not always qualify as experiential education. A major challenge in this field is the lack of shared language. Jay Roberts explains that defining ‘experiential’ methodologically can oversimplify a complex intellectual history. However, if we define it philosophically, it can become vague and difficult to apply practically.

Experiential learning is a subfield within experiential education. Experiential education is a systematic process that examines the structure and function of knowledge. In contrast, experiential learning occurs at an individual level. I will pair practice with theory to clarify these concepts.

History of Experiential Education

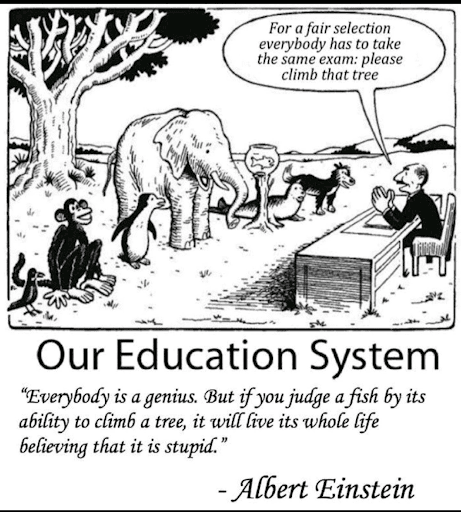

To understand experiential learning and education today, we must explore their historical roots. JohnDewey, a leading philosopher of the experiential movement, described learning as the “quest for certainty.” He led the progressive education movement, which challenged the industrial model of education. Traditional education emphasized rote memorization and conformity, depriving students of creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills.

This traditional model aimed to transmit a fixed body of knowledge, prioritizing content over personal growth. In contrast, experiential education fosters personal development by helping individuals modify attitudes and behaviors.

Experiential Learning Cycle

David Kolb introduced the Experiential Learning Cycle (ELC) in 1984. This model includes four stages: action, reflection, abstraction, and application.

Some use a simplified version: “What? So What? Now What?” This framework emphasizes reflection as a key component of learning. We do not learn just from doing; we learn through reflecting on our experiences.

An example: think back to when you learned how to ride a bike, or you were a caregiver helping someone learn how to ride a bike. Eventually you got to the day when you had learned how to balance, you learned how the pedals worked, your helmet was fitted just right. You descend the big hill with the wind blowing across your cheeks, the sun is on your back, and it is glorious!! In the distance, you see a bush – but you’ve watched cartoons before, and you know that Wile E Coyote is probably inside of the bush and going to move it out of the way at just the right time (what a rascal). It’s now like 10 feet away and you’re getting a little more skeptical…5 feet…3..2..POW!

Ouch! You’ve got snot running down your face, you might have a skinned knee, the bush is all rustled up – it’s a mess. In this scenario, did you learn how to stop your bike? No! What hopefully happened soon after the crash was that a caregiver came up to you and said something like, “Oh no! Are you okay? What happened – did you forget to use your brakes?” And then there’s the lightbulb moment! That moment of reflection with your caregiver brough the insight that you could perpetually crash into bushes to stop your bike, but that’s going to be rather painful, and you’d have to carefully choose where you ride your bike. Or, the next time you practice, you could squeeze the handbrake or pedal backwards and the brakes on your bike will stop you!

Another concept baked into the ELC is that of primary and secondary experience. This states that we don’t learn just from concrete action, but that we have an entirely different learning process that happens when you reflect upon it. Consider one of your favorite childhood toys or items. It may be very difficult to accurately remember your very first time engaging with that toy – but can you remember it? What do you notice? (That’s your primary experience.)

Now think about how you feel in this moment as you think about that toy or item. What meaning does that toy have for you after you’ve reflected on that toy for years, and how is that different from how you initially felt about it? (That’s your secondary experience – which is often where the majority of learning happens).

Application in Child Welfare

In child welfare, an experiential approach fosters resilience, independence, and positive social connections. Many young people in the system have endured grief and pain. Even the most in-depth reflection cannot always make their experiences feel logical.

Experiential education provides a guided, reflective process that connects experiences to broader implications. Activities like team-building exercises, adventure therapy, and community service projects promote collaboration, trust, and empathy. Educators facilitate reflection, helping young people apply their learning to real-life situations.

Experiential education offers structured environments where youth can practice new skills in realistic settings. For example, working in a community garden teaches planting and harvesting while also fostering patience, responsibility, and teamwork.

Experiential learning, by contrast, is open-ended and flexible. It empowers youth by allowing them to explore their interests, make mistakes, and learn through trial and error. A child engaging with art supplies may create a painting that expresses emotions they struggle to articulate. Through this process, they learn self-expression, resilience, and emotional regulation. Facilitators encourage reflection, helping children take ownership of their learning.

Experience Builds Resilience

At Crossnore’s Because of You event, Raquel McCloud shared nine factors that cultivate resilience:

- Self-worth

- Physical well-being

- Emotional self-regulation

- Cognitive flexibility

- Optimism

- Active coping skills

- Academic or career support

- Supportive social networks

- Sense of purpose or spirituality

Experiential education fosters resilience by providing structured activities that develop coping strategies and emotional regulation. Activities like low-ropes courses encourage trust and collaboration. Facilitators help participants reflect on these skills and apply them in daily life.

Community service projects and collaborative cooking lessons build social skills and confidence. Guided reflection deepens understanding, helping youth recognize their role within a community.

Experiential learning supports healing by allowing self-directed exploration. Activities like art therapy, gardening, and journaling help children express emotions and build resilience. These experiences honor their unique perspectives, allowing healing on their own terms.

A child engaged in a shared project, such as designing a community event, learns problem-solving and leadership. This open-ended approach fosters self-worth and personal growth in ways structured environments may not.

Conclusion

Experiential education and experiential learning provide valuable tools for supporting young people in child welfare. Structured experiential education builds essential skills within a goal-oriented framework. Experiential learning allows for self-directed discovery, fostering authentic growth.

A practical tool to enhance experiential practice is Jacobson and Ruddy’s 5 Questions model:

- What did you notice?

- Why did that happen?

- Does that happen in life?

- Why does that happen?

- How can you use that?

Using these questions with yourself, colleagues, or young people encourages openness to learning. Rather than imposing predetermined lessons, this approach creates space for meaningful personal growth.